Can Everyone Be a Picasso? This Is Why Some People Are Creative — And Others Really Aren’t

Posted May 11, 2021 | By admin

This article originally appeared on BrainUpFL.org, a former program of the Winter Park Health Foundation. Please continue to visit WellbeingNetwork.org for new content to fuel your intellectual pursuits and resources that support a healthy brain.

One often used definition of creativity is the ability to come up with new and useful ideas. Like intelligence, it is a trait that everyone — not just creative “geniuses” like Picasso and Steve Jobs — possesses in some capacity.

Creativity Defined

It’s not just your ability to draw a picture or design a product. We all need to think creatively in our everyday lives. Examples of daily creativity include making dinner using leftovers or fashioning a Halloween costume out of clothes in your closet. Creative tasks range from what researchers call “little-c” creativity — making a website, crafting a birthday present, or coming up with a funny joke — to “Big-C” creativity: writing a speech, composing a poem, or designing a scientific experiment.

Psychology and neuroscience researchers have started to identify thinking processes and brain regions involved with creativity. Recent evidence suggests that creativity involves a complex interplay between spontaneous and controlled thinking — the ability to both spontaneously brainstorm ideas and deliberately evaluate them to determine whether they’ll actually work.

Despite this progress, the answer to one question has remained particularly elusive: What makes some people more creative than others?

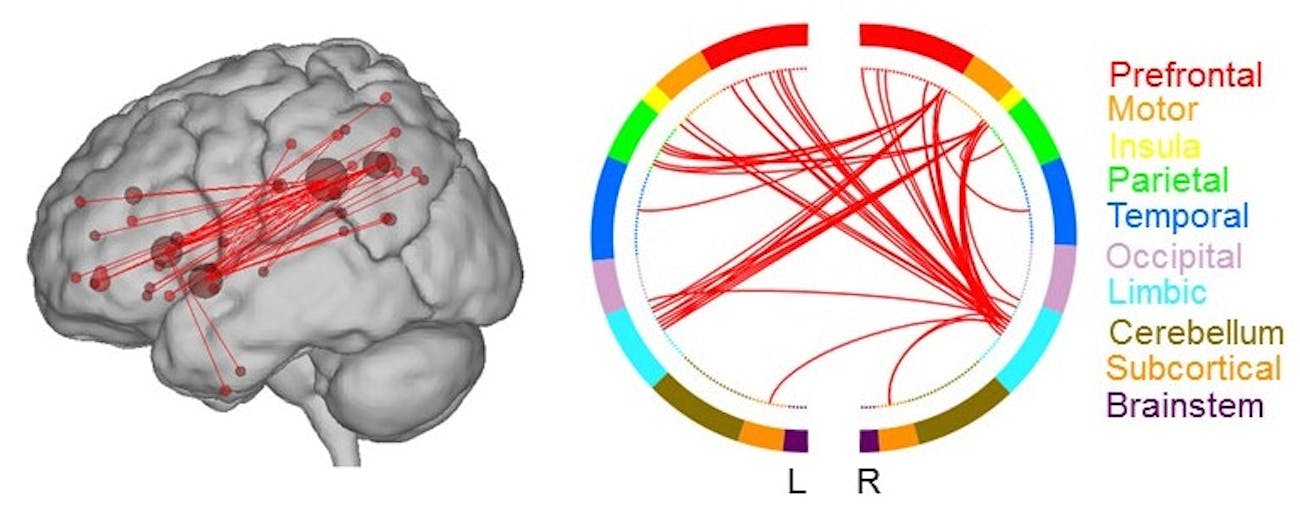

In a new study, we examined whether a person’s creative thinking ability can be explained, in part, by a connection between three brain networks.

Mapping the Brain During Creative Thinking

In the study, we had 163 participants complete a classic test of “divergent thinking” called the alternate uses task. This asks people to think of new and unusual uses for objects. As they completed the test, they underwent fMRI scans, which measures blood flow to parts of the brain.

Two renderings show the lobes of the brain which connect in the high creative network. Author provided.

Having defined the network, we wanted to see if someone with stronger connections in this high-creative network would score well on the tasks. So we measured the strength of a person’s connections in this network. Then we used predictive modeling to test whether we could estimate a person’s creativity score.

The models revealed a significant correlation between the predicted and observed creativity scores. In other words, we could estimate how creative a person’s ideas would be based on the strength of their connections in this network.

We further tested whether we could predict creative thinking ability in three new samples of participants whose brain data were not used in building the network model. Across all samples, we modestly predicted a person’s creative ability based on the strength of their connections in this same network.

Overall, people with stronger connections came up with better ideas.

What’s Happening in a “High-Creative” Network?

We found that the brain regions within the “high-creative” network belonged to three specific brain systems. These brain systems are the default, salience, and executive networks.

The default network is a set of brain regions that activate when people are engaged in spontaneous thinking, such as mind-wandering, daydreaming, and imagining. This network may play a key role in idea generation or brainstorming — thinking of several possible solutions to a problem.

The executive control network is a set of regions that activate when people need to focus or control their thought processes. This network may play a key role in idea evaluation or determining whether brainstormed ideas will actually work and modifying them to fit the creative goal.

The salience network is a set of regions that acts as a switching mechanism between the default and executive networks. This network may play a key role in alternating between idea generation and idea evaluation.

An interesting feature of these three networks is they typically don’t work concurrently. For example, when the executive network is activated, the default network is usually deactivated. Our results suggest that creative people are better able to co-activate brain networks that usually work separately.

Study Findings

Findings indicate that the “wiring” of the creative brain is different. Creative people are better able to engage brain systems that don’t typically work together. Interestingly, the results are consistent with recent fMRI studies of professional artists, including jazz musicians, improvising melodies, poets writing new lines of poetry, and visual artists sketching ideas for a book cover.

Future research is needed to determine whether these networks are malleable or relatively fixed. For example, does taking drawing classes lead to greater connectivity within these brain networks? Is it possible to boost general creative thinking ability by modifying network connections?

For now, these questions remain unanswered. As researchers, we just need to engage our own creative networks to figure out how to answer them.